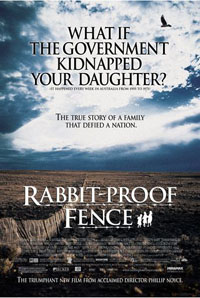

RABBIT PROOF FENCE

RABBIT PROOF FENCE(PG)

*** (out of 5)

November 29, 2002

STARRING

Everlyn Sampi as MOLLY

Tianna Sansbury as DAISY

Laura Monaghan as GRACIE

David Gulpili as MOODOO

Ningali Lawford as MOLLY’S MOTHER

Kenneth Branagh as MR. NEVILLE

Directed by: Pillip Noyce

BY KEVIN CARR

In the 1930s, the government of Australia instituted a policy that any child of mixed race living with the Aborigines could be removed from their families and put in camps. Called half-castes (for children with one-half Aboriginal blood) and quarter-castes (for children with one quarter Aboriginal blood), these children often were ripped from their families at the whim of the government.

The most chilling thing about this policy is that it did not only take place in the distant 1930s, pre World War II, computers and rock-and-roll music. The most chilling thing is that this policy continued through the early 1970s – a time most of us can remember. Unlike American slavery, this was not some distant, yet-to-be-modernized civilization that kidnapped children simply on the basis of race. This was modern, cultured society that sought to purify the white bloodline by selectively breeding out Aboriginal characteristics within three generations.

“Rabbit Proof Fence” is the story of three girls in the 1930s who are torn from their family and taken to a camp 1500 miles from their homeland. The oldest girl, Molly Craig (Everlyn Sampi), escapes and leads her two sisters away from the camp, back to their home in the Jigalong.

The title of the film comes from a fence literally built across the continent of Australia designed to keep an epidemic rabbit population from the nation’s farmlands. Molly’s family lives near the fence, so the girls soon realize that once they find the fence, they can simply follow it home. Of course, there is a chase afoot as the Aboriginal tracker Moodoo (David Gulpili), who works for the Australian government, is only several steps behind the girls.

“Rabbit Proof Fence,” which opened at the end of November in limited release and made quite a splash in the film festivals before that, has been receiving accolades from critics and moviegoers alike. And yes, the film shines light on a tough issue. However, there are some parts in the film that drag, and some of the acting seems forced and amateurish.

During one scene in particular, Molly and her sisters are torn from the arms of her mother and grandmother. Being a parent myself, watching this should have felt like someone reached inside my chest and tore my heart from my ribcage. However, I was left underwhelmed. Much of this was due to the acting, which was sporadic and minimal from the girls and melodramatically overdone by the mother and grandmother. If a kidnapping scene can’t tug at the heart strings of a parent, there’s a problem.

Another disappointing aspect of the film is an uninspired score by Peter Gabriel. An artist who has made a name for himself as a pioneer on the cutting edge, occasionally lending his musical talent to movies like “The Last Temptation of Christ,” Gabriel turns out a soundtrack that sounds somewhat canned.

One ironic thing to note is that Everlyn Sampi, who plays Molly, also had a reputation of escaping the set, one time being retrieved from a phone booth where she was trying to buy tickets back to her home in Broome

Much of the film focuses on Molly and her sisters – and this is to be expected since this is their story. However, the film does not go far enough to delve into the minds of the villains in the Australian government. What happened in Australia back then is nothing less than passive genocide. Sure, it did not involve gassing tens of thousands of Jews a day in concentration camps, but it was the calculated, systematic removal of a race.

Playing the role of Mr. Neville, the government official overseeing the camp from which Molly and her sisters escape, is Kenneth Branagh – the only really recognizable name or face in the film. Branagh, who shined as holocaust mastermind Reinhard Heydrich in HBO’s “Conspiracy,” is relegated to fussing around a desk back in his office, fretting about the elusive girls.

A more introspective look at the people facilitating the crime would have been much more powerful. Why did they do it (beyond just simple racism)? Why did it take place for so long? And could it ever happen again.

This policy the Australians had was deplorable. And the advertising for “Rabbit Proof Fence” very deliberately points out that the policy lasted into the 1970s. However, this aspect is not explored in the film. Nor is how the policy was eventually removed.

While “Rabbit Proof Fence” presents a dark spot on Australia’s history, it does little to understand it. And if we don’t understand why something happened, that is when history is doomed to repeat itself.